When the phone rang that sleepy Sunday morning, December 13, 1992, my husband, Creed, answered. Immediately, a garbled voice on the other end of the line began ranting. I made out “FSU gonna…” and “you-son-of-a…” and “Alabama ain’t…” before the caller abruptly hung up.

“What was that about?” I asked.

“Guess my Letter to the Editor was published in today’s Tallahassee Democrat,” he said, grinning.

On August 30, Alabama and FSU will kick off a home-and-home series in Tallahassee, the sixth meeting in history between the two teams. Given FSU’s 2-10 spiral last season and the lingering Bama fatigue (yes, it is a real phenomenon), it remains to be seen whether other college football fans will care enough to tune in.

But Creed King will be there. Thirty-three years have passed since he picked up his pen to refute FSU players trash-talking Bama in the media, but it seems like only last month (oh wait, it was last month)...

And that’s why come the last Saturday of August, win or lose, Creed King will be sitting in Doak Campbell Stadium until the last second ticks off the clock. If Bama players are still playing, Creed King thinks spectators should still be spectating.

As we buckle up for another wild ride on the rollercoaster that is college football, enough about the portal and NIL deals and Arch Manning (our cat’s namesake, but that’s another story)… This is a long overdue ode to the “soul of the game,” the fans. We’re not talking about fair-weather fans who give up their season tickets in a downturn or show up to tailgate but never set foot in the stadium. We’re not talking about the crazies who poison trees or teabag their rivals.

This is about the Creed Kings of the world who are loyal to their teams come hell or high tide, who believe they belong to something greater than themselves because if not, what’s the point? It's also a love letter to and about a man and his unwavering devotion to his college football team for the better part of 60 years, a span longer than most marriages.

Neal Ingram, Crawford Pounds, Creed, and David “Old Man” Herrin in 1986 on the way to the Tennessee game.

Creed and I met on the Alabama campus under what most Bama fans would consider duress: the Bill Curry era. He drove a crimson-colored Mustang and wore Wayfarer knockoffs and an old-school script-A ballcap so tattered you could see cardboard through the frayed edges of the bill. My lucky cap, he said. He had met his closest friends, Crawford and Old Man, in first grade, and the three of them lived at Colonial Oaks in the shadow of Bryant-Denny Stadium. They went to class, but their lives revolved around Saturday games and “The Coach Curry Show” on Monday nights.

One night while sitting underneath the oak tree on the Quad in front of Smith Hall, our talk turned serious. He dreamed of a family and a job. A job good enough that when he retired, he could buy an RV and strike out on Thursdays to follow the Crimson Tide from Athens to Oxford and every college town in between.

It was 1987 and I had dreams of my own and one foot already across the Mason Dixon line. I didn’t come to college for an MRS degree or to hitch my wagon to a boy who loved his Mama and Alabama football more than anything in the world.

But as we all know, romance, like sports, leads us to form arbitrary, irrational attachments, and at age 21, I fell in love. Back then, I didn’t know what today’s psychologists have actually proven: that the level of loyalty and dedication a sports fan has for their team is a good measuring stick for the loyalty and dedication they’ll invest in their close relationships. What I did know was that despite his seemingly shallow aspirations, Creed had not jumped ship in the lackluster seasons of the 1980s when Alabama football was down, so most likely he’d stay the course with me when the waves got rough. Like a vine-ripe tomato and lightning bugs, a good man is hard to find.

In 1989, when circumstances pushed our wedding to the fall, it was understood that we would schedule the event around football. I knew Creed loved me. He had just loved Alabama football longer. We married on a Vandy away game weekend. Two years later, we moved to Tallahassee.

Creed grew up in the 1970s when Alabama always won and Bear Bryant walked on water. Since those glory days, there have been many disappointments in Alabama football history, but for Creed, the only thing worse than learning that your tailgate spot of 21 years was bulldozed for “luxury student housing,” worse than watching your daughter cry over her first in-person Bama loss, worse than having your head coach meet “Destiny” in a strip club rather than on the field—the only thing almost worse than Auburn, was showing up as a Tuscaloosa transplant in Saint Bobby’s court in the early 1990s just as Florida State’s fast-break, up-tempo offenses ran the Seminoles right up the rankings—all while your beloved Crimson Tide sat benched, irrelevant, and out of breath. There’s winning and then there’s misery.

And of course, misery loves company, just not the kind that swaggers in wearing an FSU t-shirt so new you can still smell the VOCs leaching out of the iron-on letters, the kind of friend-turned foe that sits on your living room sofa drinking your Coca-Cola and eating your Golden Flake Chips, completely oblivious to the etiquette of the game itself, to the deference traditionally shown to storied programs like Alabama.

At first, Creed wrote off his new FSU friends’ unapologetic confidence to naivete: Like a dog that finally caught the car, they just didn’t know what to do with it.

Had it been the 1960s or ‘70s, Creed would have carried on with a smug assurance because back then, Bear could take “his’n and beat your’n, and then he could take your’n and beat his’n.” But this was 1991. Alabama’s last national championship was more than 10 years old, and the program had spiraled into a full-blown identity crisis. Smash-mouth, risk-averse, slowww teams like Alabama could barely keep up with the aggressive, explosive offenses that debuted in the late 1980s. Coupled with the rise of cable networks like TBS and ESPN and the pivotal 1984 Supreme Court case broke the NCAA’s television monopoly, the teams Bama had played at homecoming were now playing on television every Saturday because—let’s face it—those pass-heavy and playmaking offenses were downright fun to watch.

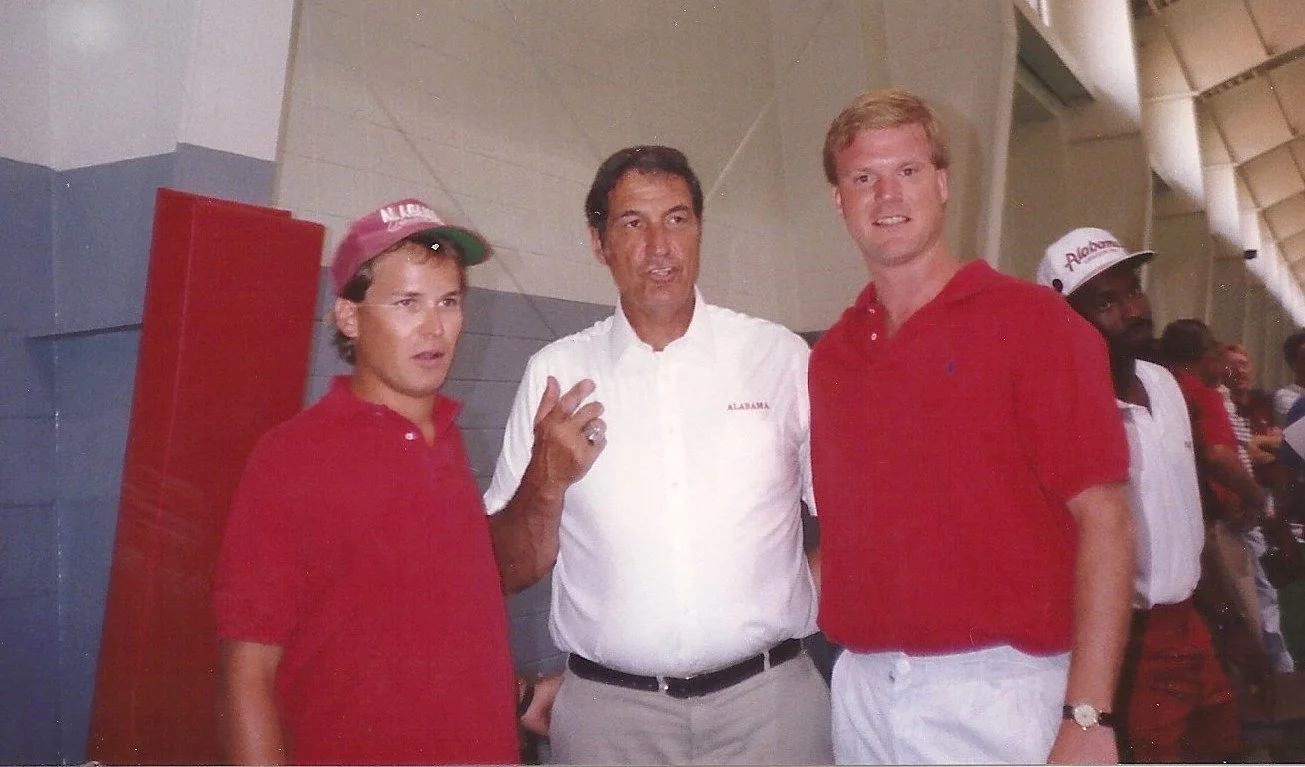

Creed and Crawford with Gene Stallings in 1992.

But then, in 1992, the 100 year anniversary of Alabama football, the Tide began to make a comeback. Was it a comeback? No one could be sure. Gene Stallings took Curry’s place in January 1990, and despite his conservative “three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust” style, Alabama couldn’t lose for winning. Except for a gawd-awful 35-0 beatdown in 1991 by the Florida Gators in Gainesville, Alabama rolled into 1992 post-season play with only one loss in the last two years.

Florida State was also on a roll. A year earlier in 1991, the Seminoles had been flying higher than the FSU Circus, ranked #1 in both polls and punch-drunk on the national attention they received as torchbearers for a new era of fast, ferocious, NFL-style play. When #2-ranked Miami came to town in November, the contest was touted as the “unofficial national championship.”

Even though Miami had won five of the last six matchups, FSU players were fearlessly confident, and they led the game until late into the fourth quarter. When Miami scored to go ahead with 3:01 left to play, Florida State marched right back down the field, converted on a fourth-and-1, and then moved to the 18-yard line after a pass interference call against the Canes. Out of timeouts and with 29 seconds remaining on a third-and-9, Bowden opted to kick—and the rest is history. The Wide Right missed field goal ended FSU’s championship run and nudged the Hurricanes toward their fourth national championship. “We’ve done our part to keep the Miami people happy,” Bowden said afterward.

The 1991 FSU-Miami “Wide Right I” game. WPTV.com.

And then, dadgummit, the same scenario played out the next year. At #3 in both AP and UPI polls, just behind Miami, the defending national champions, FSU traveled to Miami and found themselves in the lead late in the fourth quarter. And once again, Miami answered, this time with a touchdown and safety to lead 19-16. With 1:35 on the clock, FSU drove 59 yards down field into field goal range on the Hurricanes’ 22-yard line. Out of time, the Seminoles kicked—and Wide Right II. It was déjà vu all over again.

Historically, Alabama Bama fans have had a healthy respect for the Florida State program. The two teams met only three times before the 1990s and in two of those games, FSU went toe-to-toe with the Tide. The first game went as expected, with Bear Bryant’s 1965 national championship team winning 21-0 in Tuscaloosa.

The second matchup at Birmingham’s Legion Field in 1967 ended in a 37-37 tie. FSU Head Coach Bill Peterson’s pro-style offense kept Alabama off balance the entire night in a game that signaled the beginning of FSU’s move out of the shadows and into the forefront of college football.

The next day’s front page headline in the Tallahassee Democrat proclaimed that “To Seminole Fans, It Was a Victory!” “I don’t care what anyone says, a tie with Alabama is as good as a win against any other team,” one woman gushed.

Creed was only one year old at the time, but his older brother, William, attended the game with their father, Bill. “You have to remember that this was Alabama’s season opener, and we were back-to-back national champions with 17 wins in a row,” William said.

“Everyone was shocked and appalled. I don’t know what surprised me more — Bama’s complete lack of defense after 17 wins in a row or the choice words that Daddy was saying under his breath. In fact, Daddy and a lot of other Alabama fans questioned whether that game signaled something more—the start of Bear’s slump. They didn’t say it, but they were sure thinking it.” It wasn’t until 1973 after Bear introduced the wishbone in 1970 that Alabama once again reclaimed its rightful position at the top of college football.

The third meeting occurred the in 1974 for Alabama’s homecoming game. Because you can’t make this stuff up, FSU had the longest losing streak in the country and Alabama had the longest winning streak. So lopsided was the contest that Vegas didn’t even bother to post a betting line.

Yet from the opening kickoff, FSU legend Larry Key proceeded to run right over the Alabama defense, racking up 123 yards, his first 100-yard game, and the only touchdown in a near 8-7 upset. It was the first time one of Bear’s teams had failed to score a touchdown in Denny Stadium.

After the game, Alabama fans gave the Seminoles a standing ovation even as they pelted them with pint whiskey bottles (not our finest moment). When the winning Alabama kick sailed through the goal posts, FSU coaches punched and kicked holes in the walls of the Bama press box. (Ditto.) But Bear Bryant spoke for all Bama fans in a post-game interview when he gave the Seminoles their due credit. “I’ve never in my life seen a team that was so much better coached than our team,” he said.

When we first arrived in Tallahassee, Creed took pride in the fact that so many Alabama football greats had migrated south to build the FSU program. At one of the first alumni events we attended in Tallahassee, we met Vaughn Mancha, an All American at Bama and the former FSU athletic director who hired Bill Peterson and assistant coaches Joe Gibbs, Bill Parcells, and Bobby Bowden. A storyteller, Vaughn regaled us with tales about digging up palm trees in California and carrying them back to Alabama on the 72-hour train ride home from the Rose Bowl in 1946.

Vaughn Mancha played football for the University of Alabama after World War II and was one of the Tide’s star players in the 1946 Rose Bowl. The Tuscaloosa News

Vaughn Mancha was a consensus All-American center for the Alabama Crimson Tide in 1945. After two years with the Boston Yanks of the NFL, Mancha became head football coach and athletics director at Livingston State University in Alabama. In 1952, Mancha came to Florida State where he served for five years as an assistant football coach under Tom Nugent. After two years on leave in the Columbia University graduate school, Mancha returned to FSU as Director of Athletics, a post he held for 12 years. In his years as Athletics Director, Florida State moved ahead in all sports. Mancha’s administrative leadership provided the kind of scheduling and coaching that took FSU into bowl games and NCAA playoffs. The development of the balanced athletics program fielded by Florida State University today is due in no small part to the foresight and leadership of Vaughn Mancha. Seminoles.com.

Hootie Ingram, another FSU AD who lettered in football and baseball at Bama, oversaw FSU’s emergence as an elite football program before leaving Tallahassee in 1989 for the same position in Tuscaloosa.

Creed and Crawford with Hootie Ingram in 1992.

Mickey Andrews, FSU’s well-liked defensive coordinator under Bowden, played for the Bear on two national championship teams in the 1970s. And for goodness sakes, Bobby Bowden not only played his freshman year at Alabama in 1948 but went to Woodlawn High School in Birmingham with Creed’s father.

Mickey Andrews won two national titles under Bear. He earned Second Team All-American honors as a wide receiver and defensive back. He was also an All-SEC choice in baseball. In 1964, he received the Hugo Friedman Award as the Crimson Tide’s best all-around athlete. As head football coach at Livingston University in 1971 he won the NAIA National Championship.

Mickey Andrews began coaching at FSU in 1984 and served 28 years as defensive coordinator. He was recognized in 1996 as the nation’s top assistant coach when he received the first-ever Frank Broyles Award. “When I stopped coaching in ‘09, I still used some of the things we had done at Alabama.”

As FSU’s program continued to improve, the playful teasing from his FSU buddies turned to taunting. Granted, Creed didn’t make it easy on himself. The more they picked at him, the more he flaunted his devotion to the Crimson Tide. He snagged the coveted Florida “ROL T1DE” custom license plate long before the advent of specialty plates. His wardrobe was the Alabama football version of Garanimals: if the shirt was crimson, white, or featured Alabama football in any form, the bottoms naturally matched.

“He was unbearable, really,” said Ron White, an FSU alum and long-time friend and work colleague. “Every stitch of clothing down to his underwear had Alabama on it. I’ll never forget working in Maine and the guys dropping their jaws when they saw Creed walk in. At the time, they didn’t know anything about college football in the South, and they were dumbfounded by his allegiance.”

In Alabama, the past is not dead, it’s not even past. Had we not moved to Tallahassee, Creed could have continued living in a Faulkneresque reality and disregarding FSU as a team who still considered getting beat by Alabama as a victory. But surrounded by Seminole fans in a frenzy over Top 5 season finishes (which Alabama has since tied), the Bama-bashing started to take a toll. Like beating someone with a bar of soap in a sock, the bruises might not have shown, but they were still there.

The respect that Creed afforded the FSU program completely eroded at the end of the 1992 season when Alabama beat Florida in the first-ever SEC Championship. For two years in a row, FSU was denied a shot at the national championship and this time, it was Alabama who had waltzed in and stolen the berth Seminole fans considered to be rightfully theirs. Problem was, the polls and pundits disagreed. Frustrated, FSU players couldn’t help themselves and started running their mouths. Wide receiver Kez McCorvey said, “Alabama is sorry. Look at the score. Offensively, they didn’t impress me… I think we should jump ahead of Alabama.”

Defensive lineman Toddrick McIntosh predicted that Miami would beat Alabama in a Sugar Bowl blowout. And in what has become an all too common reaction for not getting their way, Seminole fans threatened to boycott the Cotton Bowl, with one fan going so far as to say that Cindy Crawford could dance nude at halftime and he still wouldn’t watch the game.

And that, my friends, is where the tide turned. Creed is not a hothead. He’s a geologist. Geologists are scientists. Scientists deal in facts. Facts are hard, as in rocks and truth. His Alabama mother had taught him that if you can’t say something nice, don’t say it at all—unless it’s true.

And so, with Crimson blood coursing through his veins, he sat down and wrote a letter. All the pent-up grief from Bear Bryant’s death ten years earlier, the frustration of 13 unlucky years since a national championship, and every last ribbing and snide remark from his new FSU friends and work colleagues converged like muddy tributaries into the mighty Apalachicola River running through Creed’s pen, ripping through sawgrass and flooding river banks in their fight to the path of least resistance to the pure, inky-blue waters of the Gulf, to the truth.

The truth according to Alabama All-American Bart Starr (who double dated with Creed’s mother, but that’s another story…) is that “Anyone can support a team that is winning—it takes no courage. But to stand behind a team, to defend a team when it is down and really needs you, that takes a lot of courage.”

Similarly, Bear Bryant loved the players who never quit trying: “They’re the soul of the game,” he said—and the same could be argued for the football fan. The NFL’s Seattle Seahawks got it right when they retired the #12 jersey in honor of their fan base. And even though I hate to shine light on Texas A&M given their association with that 77.5-million-dollar, mealy-mouthed stump of a man, the story of E. King Gill who sparked the 12th Man tradition is one of the most noble stories in the history of the sport.

Along with Arizona AP writer Corky Simpson, Creed had a gut feeling that the 1992 season would be special, and he was willing to do his part in helping Bama clench a title. A couple years before, inspired by Alabama Fan Dick Coffee who hadn’t missed a game since 1946, Creed attempted to start an attendance streak. He made it to 32 home and away games in a row before he was sidelined by the chicken pox only days before the 1991 Auburn game.

This time around, in a Samson-sized show of solidarity, Creed vowed to let his hair grow until Alabama lost. Each week, the tendrils grew longer from underneath his tattered Alabama cap, wispy reminders to his FSU buddies of the growing elephant in the room.

Such cultish devotion to a sports team is nothing new. As long as sports have been around, there’s been someone on the sidelines to make it matter. As far back as 448 BC, after brothers Demagetos and Akousilaos won Olympic titles, they hoisted their father, Diagoras of Rhodes, an Olympic boxer in his own right, on their shoulders and paraded him through the stadium. In adoration, someone in the crowd cried out, “Die, Diagoras; you will not ascend to Olympus besides!”—and with that, Diagoras collapsed at the pinnacle of fandom, overtaken in the moment by the joy and glory of what he had witnessed.

Years later, the ancient Roman poet, Horace, mentioned spectators who collected “the Olympic dust of the course.” And in a last hurrah that doesn’t seem that far-fetched in the 21st century as it does for 3rd century AD, Caicilius, an ardent fan who had travelled to the Olympics twelve times throughout his life, proudly recorded the fact for posterity on his tombstone.

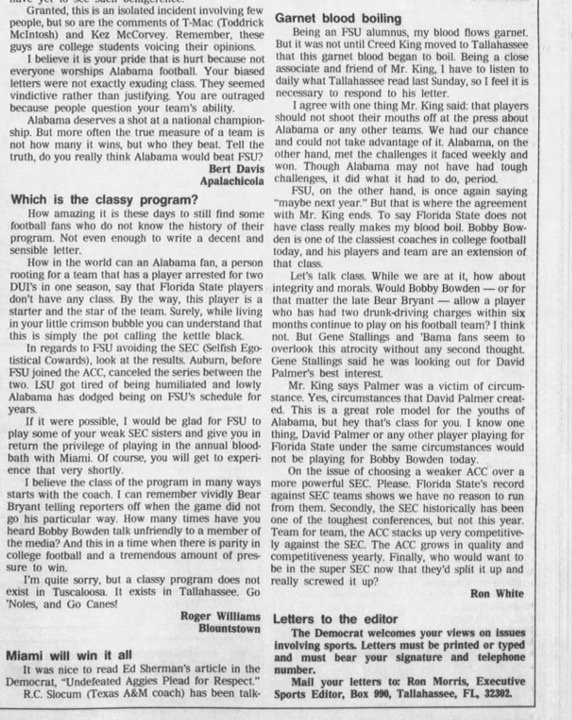

In the weeks leading up the national championship game, Creed’s letter unleashed a torrent of responses. “Miami will beat Alabama by 20 points in the Sugar Bowl, and that should be enough to make Miami the best team in 1992…” Another wished for Bama to have the privilege of “playing in the annual bloodbath with Miami … of course, you will get to experience that very shortly,” the fan commented.

Not one to let other teams do more trash-talking than their own, Miami soon joined in the banter. “Alabama's cornerbacks don't impress me one bit, spouted Miami Receiver Lamar Thomas. “They're overrated. Real men don't play zone defense, and we'll show them a thing or two come January 1st.”

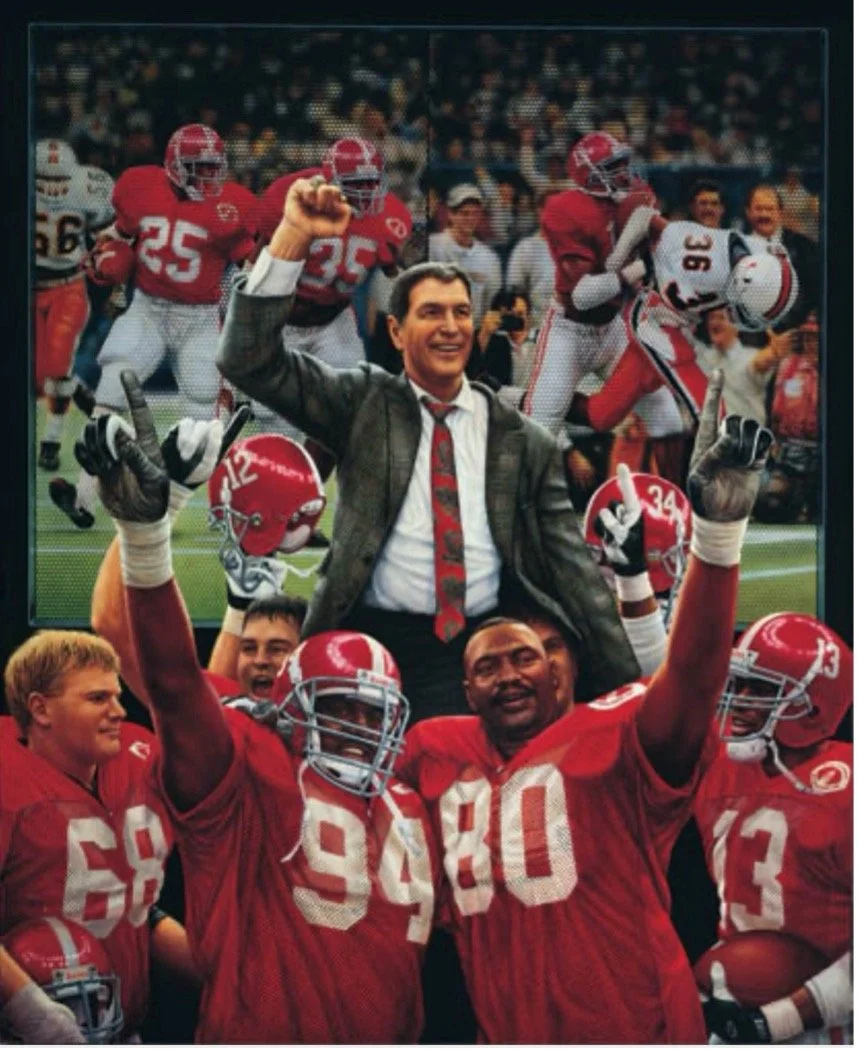

Come January 1st, Creed and Crawford settled into their seats in the New Orleans Superdome, stone sober and nervous—nervous, that is, until Heisman quarterback Gino Torretta threw three interceptions and Alabama ran straight through the Canes for a 34-13 finish and the program’s 12th national championship. “He made some good throws,” Head Coach Gene Stallings said of Torretta, “and we got some of them.”

As for Lamar Thomas, he showed Bama a thing or two alright. His likeness now hangs in the home of Bama fans the world over, immortalized in Daniel Moore’s painting, The Tradition Continues, with George Teague’s “The Strip” considered one of the all-time greatest plays in Alabama football.

Daniel Moore’s “The Tradition Continues.”

After the game, Bama fans piled into the French Quarter, swept away by a Tidal wave, feet barely touching the ground. “That was nothing but 150 percent Gene ball,” Creed said, reflecting on the game. “I don’t think we would have won if Miami hadn’t run their mouths. Our guys kicked it up a notch because of all the talk. We wanted it a lot more than Miami.”

Back home in Tallahassee, the Tally Tide Alumni Club celebrated at a local bar. I made a homemade red velvet cake with cream cheese frosting for Creed to take to work, unable to resist writing “Roll Tide” in red icing across the top. Alabama fans flooded the Democrat with letters avenging the Tide. And for the first time in 13 months, Creed got a haircut.

There’s been a lot of football since that 1992 season: Heisman trophies, retirement for two of the greatest to ever coach the game, boosters with more money than sense, probations and vacated victories, the textbook scandal, the strip club scandal, the Dillard’s clothing scandal, the crab legs scandal, and an astonishing 10 national championships between the two teams. In the dog world, there are as many “Bowdens” as there are “Bears” and “Sabans.”

When Alabama and FSU played a fourth time in Jacksonville in 2007, Alabama lost 21-14. On the way back to Tallahassee, our chartered bus full of Bama and FSU friends broke down on the side of I-10. Was it an omen of things to come? If only Creed had known then what we know now: that Bama’s new coach that year, Nick Saban, would bring about a resurgence of Bama football so dominant and breathtaking that sportswriters would take to the Bible to aptly describe “the terror and awe of watching a behemoth” that would define Alabama football for the next twenty years.

After the 2013 Iron Bowl “Kick Six” game, Creed came home to find a 10-foot giant blowup tiger on top of his house.

Coming off back-to-back national championships in 2011 and 2012, Alabama led the polls for the entire season of 2013—until Auburn won the Iron Bowl with the Kick Six and no time left on the clock. Creed drove straight home from the game only to find a 15-foot tiger on the roof of our house. The mouthy text he shot off to his group chat launched an all-out war that lasted for weeks. He refused to watch the Auburn-FSU national championship game. Instead, he took down Christmas decorations and packed them away for next year.

The last time the two teams met was 2017 in the Kickoff Classic in Atlanta. Alabama won 24-7. It wasn’t even a contest, bless their hearts.

So here we are, 400 games and 33 years since Alabama’s 1992 national championship win. The first acorns have fallen, and if you stay outside long enough in the evenings, you’ll catch an ever-so-slight breeze cutting through the humidity. It’s football weather, Creed says.

A collage of Letters to the Editor from the Tallahassee Democrat still hangs in our hallway. Creed’s crimson-colored truck still sports his “ROL T1DE” license plate. He still wears a tattered Bama cap almost everywhere he goes.

The exchange of letters between Alabama and FSU fans in 1992. Tallahassee Democrat.

Between the games, Creed’s finest fan moments shine brightest in our daughters. Growing up a Bama fan in Seminole territory toughens a girl, kind of like being a Democrat in Alabama. Saban’s Game Changer video played in our minivan on morning drives to school. The girls’ Saturday lemonade stands closed for Bama games.

L Creed and Lily Sweet, our oldest daughter, at the BAMA-Notre Dame 2012 National Championship in Miami.

R The girls’ lemonade stand: “Sorry, we are Bama fans. We went inside to watch the game. Be back tomorrow.”

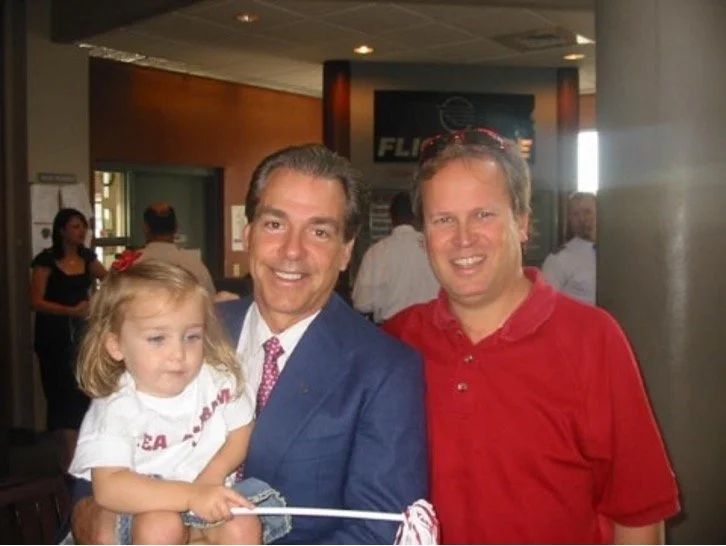

When Nick flew to Tallahassee on a 2007 recruiting trip, Creed took off work and met him at the airport with our youngest daughter, now a junior at Bama. Our middle daughter wrote a 5th grade English paper on “Scam Newton.” Our eldest daughter’s first words were “Roll Tide,” the same daughter who grew up sitting between her father and godfather at Bryant Denny Stadium, falling so hard for football that she’s now an NCAA Division I Director of Recruiting after stints at Ole Miss and Texas (hence the origin of Arch the cat)—and still mad that she’ll never have the chance to work for Nick. Creed’s proudest accomplishment? None of his girls went to Auburn—or FSU.

Tallulah King, Nick Saban, and Creed in 2007 at the Tallahassee airport, back when you could still track the Alabama football airplane’s flight path.

I’d like to say that Creed has mellowed after so many years of back-and-forth with his FSU buddies. Nothing could be further from the truth. Time doesn’t change a man; it just makes him more of who he is, and right now, Creed King is annoyed, annoyed that a team-jumping quarterback has the gall to practically promise an Alabama defeat. I would expect nothing less. As time has proven, the Creed Kings of the world aren’t extreme; they’re steady. Unwavering through thick and thin, they’re the ones who pass down values of loyalty and pride along with their season tickets and the family Bible. They form the backbone of their teams—and their families. You might not know our Creed King but no doubt you know the Creed King for your team.

The kickoff game on August 30 is the first time Alabama will play in Tallahassee. We’ve already hung our Alabama flag, pulled out the bronze statue of Bear, and placed the porcelain red elephant centerpiece in the middle of the table in preparation for the Castellanos Paella Party we’re throwing the Friday night before for our Bama and FSU friends.

The next day, Creed will be sitting in Doak Campbell Stadium doing what he does every Saturday in the fall. He’ll get to hear FSU’s catchy war chant in person and see the pretty horse that parades out before the game. But even he admits that he’d prefer a more evenly balanced matchup. “It’s no fun to diss a 2-10 team,” he says. If FSU’s dry spell stretches out to match Alabama’s longest period of time between national championships, it will be five more years before FSU wins a nattie.

Even if Alabama loses, it won’t be pretty, but Creed King will still believe that we’ve got something y’all don’t. Losing doesn’t make him want to quit—it makes him want to fight that much harder. Alabama has never been “nothing but a winner,” and if Bear said it, it must be true.

But who knows, the Seminoles might pull off an upset. When it comes to getting a break on the field, FSU is a lot like Auburn, and as Creed’s father, Bill, always said, Auburn is luckier than a dog with two dxxks. But that’s another story….

Epilogue: Final score: FSU 31 Alabama 17… Six weeks later, “F*ck You Bama! still rings in Creed’s ears after an excruciating loss made all the worse by the fact that at this point in the season, FSU has lost 3 games while Alabama has managed to remain a one-loss team. But just wait until next year…